* We will be reprinting articles from our past newsletters. This article appeared in March 1966. It has not been updated or altered in anyway.*

By Jean H. O’Hara

Descriptions of America have been recorded in letters, newspapers and books since Captain John Smith sent his impressions of the new lands home to England where they were published in 1608. Through complimentary or derogatory comments, these impressions of native or foreign travelers are especially valuable in any study of the early communities of our country. In many instances they provide the only insight into the past of areas on which no other records are available.

Most of the earliest writers were transients, and through their words it is possible to trace the growth of Schenectady from a frontier trading village into a thriving commercial town long before the Civil War and the industrialization which transformed it into a city of the twentieth century.

Missionaries and explorers, the earliest of non-native visitors, were moved to remark on this beautiful and fertile valley even before Arendt Van Curler envisaged a settlement on these flatlands. Others obviously shared their enthusiasm, for in 1661 a courageous few agreed to build homes in the wilderness. By 1680 travelers to “Schoonechtendeel” found a village of thirty houses and one of these, Jasper Danckaerts, was enthusiastic in his praise of its rich soil and wheat crops but critical of its religious atmosphere. He noted in his Journal that “…this place is a godless one, being without a minister and having only a homily read on Sundays…”

Little more than a decade had passed when the shocking massacre of its inhabitants made Schenectady a topic for discussion throughout the colonies and abroad. Reports on the holocaust promoted visits from the curious and those on official business, including Governor Henry Slaughter, who viewed the village on June 30, 1691 and later reported that he “…found that place in great disorder, our plantations and Schenectady almost ruined and destroyed by the enemys during (sic) the time of the late confusions here. I have garrisoned Schenectady…”.

With the advent of resident troops, the village advanced from being little more than a trading settlement to a frontier military post, worth of being mentioned in official reports to England. The importance of this northern frontier focused ever- increasing attention on this area. In 1698 Col. William Romar was commissioned by Governor Bellomont to inspect the northern fortififications, and he reported that Schenectady was “…neglected, built of wood and palisades of poor defense…”.

Because of its strategic locations, the village on the banks of the Mohawk became the center for early negotiations with the Indians, and was often visited by emissaries from the Sachems and the Royal Governors. Drawn by Conferences with the Five Nations, Governor Edward Lord Cornbury honored Schenectady with a visit in July of 1702, and Governor Robert Hunter arrived in August of 1710.

In November of 1710, Governor Hunter returned with on John Bridger, who had been commissioned to seek wood for His Majesty’s ships. England drew upon the natural resources of her colonies to supply naval stores for the vessels of the Royal Navy. Aside from their importance to the colonists, the vast forests along the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers attracted the attention of the Royal authorities. Mr. Bridger reported a successful journey by writing to his superiors that”…I have with the Governor been up Hudson’s River at Albany and Schinectedy (sic) and have seen and viewed several great Tracts of Pitch Pine proper for making Tar, Pitch…”.

Visitors during these early years of the 18th century were confined mainly to the above mentioned officials, courageous pioneers migrating westward into the wilderness, and military personnel passing through to engage the enemy during the French and Indian Wars. But interest in exploring America encouraged both native and foreign travelers to visit the northern frontier. Scientific studies brought Europeans such as Peter Kalm into the area around Albany, while an inquisitive nature prompted a physician from Maryland, Dr. Alexander Hamilton, to accompany an Albanian surveyor to Schenectady on June 28, 1744. His description of the approach to the village from the Albany Road is most poetic:

“…(Schenectady) is a trading village, the people carrying on a traffic with the Indians – their chief commoditys (sick) wampum, Knives, needles and other such pedlary ware. This village is pretty (sic) near as large as Albany and consists chiefly of brick houses, built upon a pleasant plain, inclosed all round att (sic) about a Mile’s distance with thick pine woods. These woods form a copse above your head almost all the way betwixt Albany and Schenectady, and you ride over a plain, level, sandy road till (sic), coming out of the covert of the woods, all att (sic) once the village strikes surprisingly (sic) your eye, which I can compare to nothing but the curtain rising in a play and displaying a beautiful scene.”

The end of the Seven Years War brought resumed migration of settlers along the Mohawk and an increase in visitors, including many distinguished persons on their way to confer with Sir William Johnson. In the winter of 1760, Sir William’s brother Warren, passed through – apparently amazed that the Mohawk river was frozen enough to permit crossing on foot at Schenectady. He was not favorably impressed with the settlement, for he referred to it as “…a little dirty village…”.

A more complimentary description of the village and its growing commercialism is found in the comments of Col. Thatcher T. P. Luquer on his arrival in 1767 – when there were approximately 300 houses and about 3000 inhabitants. His words also illustrate that the growing British influence in New York had also reached this outpost of civilization-

“…The houses, which are mostly of wood, are built in the Dutch taste, there are some good edifices, lately built, after the English manner. Along the river are storehouses from which the goods for the upper trade are shipped in bateaus…Here are built all the bateaus for the transportation up the Mohawk River, and a number of the inhabitants of the towns and settlements on the banks of the river are employed, and get their livelihood by navigating them. Three men are commonly in each bateau, they are paid from Schenectady to Oswego 5 pounds a man…”

Despite such lucrative sources of income, a lively trade with settlers and Indians up river, and fertile soil for crops, villagers at this period were still dependent on older settlements to the East for some items. Richard Smith, traveling through in 1769, mentions in hi Journal that “…The Tounspeople are supplied altogether with Beef and Pork from New England most of the Meadows being used for Wheat, Peas and other Grain…”

In the following year the inhabitants of Schenectady were exposed to the religious experience which affected all colonies in the years prior to the Revolution. The Reverend George Whitefield, harbinger of the Great Awakening, honored villagers with a visit in July of 1770. He in turn “…was struck with the the delightful situation of the place…” and his enthusiastic reception.

The American Revolution transformed the quiet village into a rendezvous for militia and regulars marching westward and a haven for refugees fleeing from Tory and Indian raiders. During this period General George Washington was certainly the most distinguished visitor, but there were others of importance including the Marquis de Chastelux, one of the many Frenchmen who gave assistance to the American cause. The Marquis was particularly interested in colonial life and inspected the Oneida encampment while in Schenectady in 1780.

He recorded a sympathetic view of the state of these Indians for he found the settlement”…nothing but an assemblage of miserable huts in the woods along the Road to Albany. The Framework consists of only two uprights and one cross pole, this covered with a matted roof, but is well lined with a quantity of bark…”. This encampment was destined to be an eyesore for both residents and transients for many years.

With the coming of peace the movement of settlers westward began again, with the Mohawk valley a natural passageway to Ohio and beyond. Schenectady prospered through trade and reached new importance as a transportation center. One of the many making use of its facilities in 1793 was John Heckewelder, who travelled in the interests of the Moravian Church. He found a village which had grown to include almost 400 houses, 3 churches and an Academy. His description illustrates a vigorous atmosphere:

“…The Inhabitants of this place (seemingly generally pretty Industrious) are likewise chiefly Low Dutch, and appear pretty Sociable. The keep up a Number of light Waggons to transport the Produce brought down the River to this place, to Albany, to which place they go and return the same day. The 8 new boats made here for the purpose of transporting our Baggage, and for our Use to Niagara being loaded we sat (sic) off at 3 in the Afternoon, with 30 hands from hence to work the boats.”

But work was intermingled with pleasure along the banks of the Mohawk, and villagers joined with the rest of America in annually celebrating the anniversary of its Declaration of Independence. In the early days of the 19th century a new awareness of nationalism swept the country, and a Scotsman, J.B. Dunlop arrived in Schenectady on July 4th, 1810 – in time to witness its celebration of the holiday. With glowing words he wrote:

“…There was a grand display of fire works on the Mohawk river, the banks of which, as well as the beautiful bridge over it, were crowded with people, whilst innumerable boats, filled with the genteel class, moved upon the smooth surface of the river to the reverberating echo of a band of music which filled up the intervals between each fire rocket with martial music. The moon shone beautifully bright on all…”

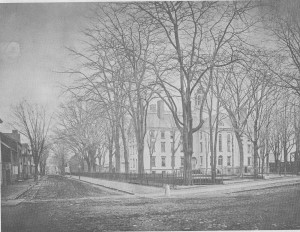

The bridge mention above, which was built in 1809, attracted an even greater number of visitors who wished to view the latest and, in the opinion of many, the great greatest accomplishment of its designer Theodore Burr. Another attraction was Union College and one typical traveler of 1818 who expressed interest in the institution was William Darby, who passed through the town on his way from New York City to Detroit. He made special note of Schenectady’s buildings and its college by commenting that “…Many of the buildings are large, expensive and elegant…For my own part, I viewed the buildings composing the three colleges which bear the name of Union in Schenectady, with a similar reverence, with which I had formerly felt passing Cambridge, Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Dickinson. Those, and other such edifices, are the true temples of reason.” During the following year many of the town’s buildings were destroyed in the disastrous fire of 1819.

Mr. Darby also found exceptional the regularity with which properties and streets were laid out. Its design gave credit to the first proprietors, whose orderly division of lands avoided the haphazard growth found in most other early settlements in New York.

While construction of the Erie Canal made it possible for boats to navigate eastward to Albany, most travelers found it easier and quicker to ride by stage or carriage to Schenectady for embarkation. This meant additional income for the coffers of local businesses, as the importance of canal transportation advanced. Typical of the many who chose this method of moving westward was the notorious Mrs. Frances Trollope, who wrote”…The first sixteen miles from Albany we travelled in a stage, to avoid a multitude of locks at the entrance of the Erie canal; but at Schenectady we got on board one of the canal packet-boats for Utica…”

Some comments on the American scene were written for private viewing while others were produced for their commercial value, and by the 19th century any publication containing information on America was guaranteed to experience immediate popularity abroad. Mrs. Trollope found it even more profitable in 1831 to produce a scathing report of her travels in the “Domestic Manners of the Americans”, a book which made her name an infamous one for many generations.

A fello-countryman and admirer, Asa Greene, an ex-barber to the King, followed Mrs. Trollope’s example within two years. Among his uncomplimentary remarks about America, he wrote of Schenectady: “…The only thing worthy of note here, is a college, as it is dominated in America; which means nothing more than a school where a parcel of boys learn Latin and Greek, and a few other things; but as I am credibly informed, are never whipped, as the boys are in England…”.

But Mr. Green had the exciting experience of riding on the newly opened railroad between Albany and Schenectady, the western terminus of which was the imposing Roman-style depot on a bill east of the town. The traveler, who rode at the rate of fifty miles an hour, had mixed emotions about the journey, and commented; “…To tell the truth, this is quite an easy mode of traveling; and were it not for the vile republican company with which the rail-road cars are continually crowded, would be a very agreeable one…”.

But the “republican” atmosphere in America by this time constituted one of largest elements in the formula which produced national growth and democratization. The railroad on which Mr. Green travelled was soon to change the complexion of Schenectady, and by the time of the Civil War the town had grown to the point where it was ready for the industrialization which was to follow – ready to retain its importance in a modern world.

Leave a comment